The Orrington Historical Society invites you to our annual Christmas Gathering at our home in the historic Grange Hall. Come tour the decorated hall, enjoy holiday refreshements, see the displays, tour the many new building updates and listen to holiday music. It’s the perfect time to gather with your friends and neighbors and spread holiday cheer!

You’re invited to our annual Christmas Gathering

Comments Off on You’re invited to our annual Christmas Gathering

Filed under Uncategorized

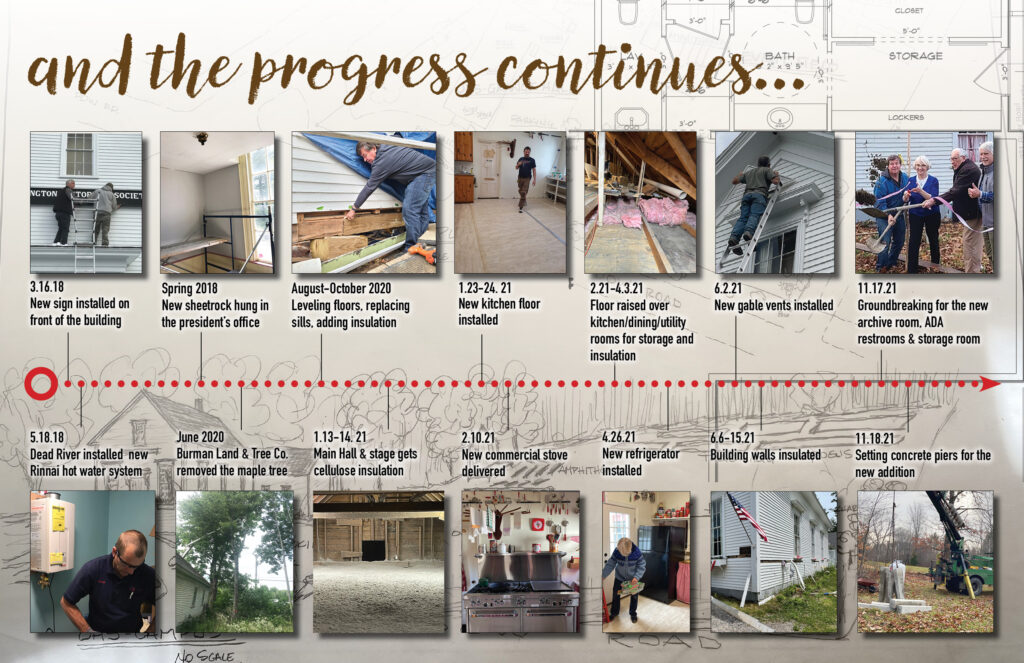

Our support is going through the roof!

We are almost there!

Thanks to the many in our community who have volunteered significant time and funds resulting in improvements to our Orrington Historical Society’s (OHS) building and grounds over the past six years. To date, approximately $195,000 has been raised, plus tens of thousands of dollars worth of in-kind

contributions of materials, expertise and labor. Because of these generous contributions, the OHS is pleased to announce the Family Phase of fundraising is complete and we are now launching our final Public Phase financial appeal!

To take us over the top, $75,000 is needed to complete the projects below that will meet the needs of our community and support the OHS’s mission:

• Water purification system for the new ADA restroom & kitchen

• A new Main Hall heat pump system along with weather-tight, energy efficient window panels in all areas

• Complete the valuable records storage room above new archival addition

• Finish the vintage kitchen, dining room & utilities area work to allow community activities

• Resurface and install drainage in the parking area

• Relocate the Fairgrounds Building to the Dow Road campus to house our many large historic artifacts

• Build the outdoor amphitheater for weddings, theater productions, musical events and more

• Develop programming for children and families focused on the history of Orrington’s rural life.

This final phase needs financial support of $75,000. We have received a generous $20,000 match donation to get us started! Won’t you please consider a contribution today? And please share this message with all your family, friends and co-workers. Every little bit helps! You can help us blow our fundraising through the roof!

Please send donations to:

Orrington Historical Society

P.O. Box 94

Orrington, ME 04474

or donate securely online at www.GiveSendGo.com/OHS

Comments Off on Our support is going through the roof!

Filed under Uncategorized

Azubah Freeman Ryder

Summarized by Judith Frost Gillis from an Orrington Centennial publication, June 1888, A short sketch of the Life of Azubah Freeman Ryder, A Centenarian and from Kay Washburn’s 1975 Bicentennial tribute, The Story of Samuel and Azubah Freeman Ryder, Early Settlers of Orrington, Maine.

Azubah Freeman Ryder was born in Eastham, Massachusetts on January 5, 1784. In November 1788, four-year-old Azubah arrived in South Orrington on a sailing vessel with her parents, Timothy and Zeruiah Nickerson Freeman, and her nine siblings. She was the youngest daughter. Timothy Freeman had built his cabin, arranged for provisions, and cut firewood to last the first winter, but he could not have prepared for his wife to die the next month giving birth to the Freeman’s last child, Baby Thomas.

In the spring of 1800, there was a memorial service for George Washington who died the previous December. Around a symbolic open grave, stood sixteen girls, sixteen years of age, representing the sixteen states of the young country. Azubah was one of the girls. A sermon was read. Participants walked slowly around the grave, scattering flowers, and singing a hymn composed for the occasion by an Orrington citizen.

The town was prosperous, and Azubah was hired to teach at the Pine Top School near Swett’s Pond, and daily she walked the mile to and from the schoolhouse in the woods. Samuel Ryder from Provincetown had built a successful store on the wharf and a two-story house on a point in South Orrington overlooking the Penobscot. Among his children was a son Samuel, who went to sea at a young age and became captain of his own ship while still in his twenties. A discreet courtship occurred between Capt. Samuel Ryder and Miss Azubah Freeman. They married in 1807, and Azubah continued teaching until giving birth to her first child.

During the War of 1812, the U.S.S. Adams had done much damage to British naval shipping, and the British wanted to capture the ship and its officers. Herself damaged, the Adams was being towed up the Penobscot in a futile attempt to save her and her 24 guns. The Americans scuttled the Adams to keep her from the British. In the safety of darkness, Azubah’s husband, Samuel Ryder, rowed four of the ship’s officers to Boston. Samuel had been given up for dead when he finally returned to his wife and family.

On September 3, 1814, the American militia were marching up the road from Castine, turned right, and disappeared in the woods towards Goodale’s Corner. The British lost the men’s trail and continued up the main road. Azubah saw the uniformed men passing by her home and gathered her children to run through the woods towards Orrington Center, warning residents that the BRITISH WERE COMING. Azubah became the Paul Revere of Orrington, Massachusetts! That night at the Orrington Center home of Capt. Barzillai Rich and his wife, Azubah safely gave birth to her fourth child, a daughter named Deborah. Meanwhile from the Penobscot River, the British Sloop of War Sylph, chased the U.S.S. Adams while firing their cannons at Hampden and Orrington. At Orrington Corner, Capt. William Reed was shot and killed. He is buried with his wife Elizabeth at Riverview Cemetery in North Bucksport.

Azubah Freeman Ryder died on September 30, 1888 at age 104 years, eight months, and twenty-five days. She was the oldest inhabitant of Orrington and thought to be the oldest person in New England. She outlived nineteen Presidents, five of her eight children, and her husband Samuel. Azubah was buried beside her beloved Captain in the old cemetery on a hill, located on what was the farm belonging to Frank Hoxie. These words were written on her stone:

Her pains all o’er, her sorrows past,

Life’s sermon laid aside,

She reaps the great reward at last,

In heaven to abide.

Filed under Articles

They Refused to be Forgotten (Orrington Gazette, c. 1975)

by Kay Washburn

Thanks to Carolyn Crawford, Buster and Betty Albert, Raymond Perkins and George Fairfield for help on this article.

[Transcribed by P. Bickford-Duane, 11/6/17.]

On May 26th, Memorial Day, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, Post No. 4527 of Orrington, held memorial services at Pine Hill Cemetery, at the gravesite of George LeGasse, a veteran of World War 2, who served in the Coast Guard. There was a brief address by Eric Brennan, emphasizing the VFW pledge to “honor the dead by helping the living.” The reading of Gen. Logan’s General Order No. 11, issued on May 5, 1868, is always part of the service, as his statement hits the essence of the order. Then the post commander Vern Wardwell placed a small wreath on the grave, the symbol of remembrance, and three officers of the Post each placed a flower: a white flower, denoting purity; a red flower, for the heroic dead; and, by an officer of the Women’s Auxiliary, a blue flower, denoting eternity. Finally the commander laid a flag, the emblem of the nation, on the serviceman’s final resting place. (At seaside posts, wreaths are tossed overboard for those buried at sea. Betty Albert remembers, when she was 5 or 6 years old, in her home town of Cohasset, Mass., she had the honor of tossing on the water the wreath of lilacs her mother had made for the occassion.) The grave to be decorated is picked by the Post Commander, and may vary from year to year. Often it is the grave of Maurice E. Miles, for whom the post is named, and the only Orrington man to be killed in World War 2. But the important thing is that they are remembered, by their comrades in arms who survived them, and, persumably, by the country they served so nobly.

It wasn’t always thus. In 1899, Spanish-American war veterans had just returned home from the Cuban and Philippine battle fronts. They were young fellows, but they were prematurely aged by the ravages of tropical fever, bad food and medical neglect. They were the fighting men who had been victorious against foreign enemies. When they returned home they found that apparently no one cared. They were truly the forgotten. They received their discharge pay, $15.60 per man. Then they were turned loose as civilians – free to do as they pleased. They should have been happy but they couldn’t be. The men were ill, some of them desperately ill. They were too sick to work steadily. Most of them quickly became penniless. There were no government hospitals for the disabled, no helping hands, no financial assistance. It was a picture of deplorable neglect. Finally some of the Spanish-American war veterans decided that something must be done for their sick and needy comrades. They realized that they themselves would have to start the ball rolling. So, on the night of September 29, 1899, a young veteran of the Cuban campaign, James Romanis of Columbus, Ohio, called together about 12 of his veteran friends. They met in a back room of a tailoring shop in Columbus. And that was the very start of the VFW, the first veterans’ organization since the Civil War.

The objects of the Veterans of Foreign Wars are “fraternal, patriotic, historical and educational; to preserve and strengthen comradeship among its members; to assist worthy comrades; to perpetuate the memory and history of our dead; and to assist their widows and orphans. To maintain true allegiance to the government of the U.S.A. and fidelity to its constitution and laws; to foster true patriotism, to maintain and extend the institutions of American freedom, and to preserve and defend the U.S. from all her enemies whomsoever.”

Raymond Perkins joined the VFW while still serving in the armed forces overseas during World War 2. At the close of the war, he joined Norman N. Dow Post No. 1761 in Bangor, the nearest one to his home town. Then, on Saturday, Dec. 1st, 1945, at a supper installation and dance at the Grange Hall, Orrington launched its own Post, No. 4527, the Maurice W. Miles Post. Raymond Perkins was elected first Commander. By a wonderful stroke of luck, the Union Hall Corporation decided to dissolve, and deeded its building over to the “Vets,” so they had a fine meeting hall free of charge.

The VFW have contributed much to the community over the years. They were the moving force in organizing the local Senior Citizens Club. They sponsored Old Home Week for 21 years in a row. Incidentally, we’re glad to note that Old Home Week is being reactivated as part of the BiCentennial observance, and we’re sure the “Vets” will be very much a part of it as always.

Betty Albert remembers the time her father, Ralph F. Hines, here on a visit from Cohasset, Mass., played the part of the Unknown Soldier in an Old Home Week parade. He lay on a catalfaque, a cross at his feet with helmet and rifle laying against it, symbolizing those fallen in battle. The kids thought he was really dead. He got a big kick out of it. “It was the last great thing my father did,” says Betty.

No mention of the VFW is complete without a report of the Military Order of Cooties, the honor degree of the organization. Founded in Washington D.C., in 1920, the primary function of the “Cooties” is work in Veterans’ hospitals. “The objects of this organization,” we are told, “are to be the official honor degree of the VFW, to promote social and reunion features among its own members, and to keep alive therein the spirit of optimism and humor, so characteristic of the American serviceman.” That last part, “the spirit of optimism and humor” covers a multitude of, shall we say, sins? Well, at least, practical jokes and eccentric behavior. The Orrington Pup tent, Miassis Dragon No. 19, containing only about 20 members out of a VFW roster of 80-plus, contribute a “spirit of optimism and humor” out of all proportion to their numbers. They travel a lot, appearing in parades and conventions throughout the state and the country. They visit the Veterans’ Hospital at Togus, taking gifts and remembrances, putting on shows, and in general contributing to the patients’ well-being. The four flags at Union Hall (the U.S., Cootie, VFW and State flag) have all marched in national conventions in New York City.

In State conventions, the Orrington group have been winning consistently the competitions for best color guards. Once, at Rockland, a jealous group decided to get even. The parades of the Cooties are always held at night – just one of their idiosyncrasies (we’ll describe some more later), so, in the dark, they tied a fishline across the road from telephone pole to telephone pole. As the boys of Miassis Dragon came stepping smartly along, they walked into the fishline and all four proud banners hit the dirt.

At that same parade, a woman motorist was held up at a side street as the parade was passing by, and irritatedly blew her horn at the delay. The Cooties picked the car up and calmly removed all four tires.

It was in Rockland, also, that the Orrington Pup tent held an impromptu swimming meet in their hotel pool. Dick Godfrey led off, doing a perfect back flip. Buster Albert, not to be outdone, decided to try a front flip, supposed to be much harder. He did a perfect one. They felt that these great dives were furthered enhanced by the fact that they were both in full uniform at the time.

Wally Bowden probably remembers the time he had a brand-new Rambler, and, on a trip to Togus, locked his keys in the trunk. They had to spring the cover up with a tire iron to free them.

The Cooties are born competitors – they once entered a fireman’s muster at Bar Mills, even though they weren’t firemen, and were beating all competition, causing so much consternation among the real firemen that they were disqualified.

As we said before, Cootie parades always start at night, and are preceeded by breakfast. Backwards, yes – but that’s the way they do things – backwards. When they take attendance, if you’re present, you’re marked “absent.” In voting, if you approve of a motion, you vote “no.” Likewise a “no” vote means “yes.” Balloting is done with coins, i.e., you drop in a penny. If you vote “yes,” which means “no,” you have to put in a piece of silver. All money thus raised goes to Togus. In making a motion, the motion is first seconded, and then made.

Betty Albert remembers one parade when the Orrington Cooties drove a ‘64 Caddy convertible with 21 people riding in, or on, it. In that same parade, she remembers someone had a Model T Ford with no brakes; the passengers had to drag their feet to stop it. Was that the Herring Chokers of Eastport? The Pooper Doopers of Skowhegan? The Ants in Pants? All pup tents have similar irreverent titles, but we doubt if any of them can beat our modest little Orrington group. The Cootie and VFW convention this year will be June 13, 14, and 15 at Boothbay Harbor.

And now for the ladies. As Carolyn Crawford told us: “Our community service is tremendous, but we don’t talk about it, so few people realize the scope of our activities. Cancer is our chief aim, along with the Voice of Democracy Essay Contest. Other projects include Buddy Poppy Day, Community activities, Keep America Beautiful, Safety, Legislative, Maine Scholarships, the National Home for orphans and some widows of veterans, Rehabilitation, Hospital VAVS, Youth Activities.”

Cancer research is the most vital work of the Auxiliary. Last year they contributed $100,000 to build the Dorothy Mann Memorial Unit at the Jackson Lab. For construction and furnishing of Labs, research library and other buildings, the Auxiliary has contributed $200,000. In fact, if it had not been for the Ladies Auxiliary of the VFW, the Jackson Lab may never have been rebuilt after the fire of 1947.

In this year’s 28th annual Voice of Democracy contest, about 5,000 students in 8,000 public schools and parochial secondary schools participated, from the 10th to the 12th grades. State scholarships totaling $1,500 and National prizes totaling $22,500 were awarded.

One of the Auxiliary’s projects which we found most appealing and interesting is the annual birthday party for the Statue of Liberty. Yes, that’s right – every year, on the anniversary of the unveiling of this great statue, the gift of France to the U.S. in 1886, the VFW Auxiliary celebrates the occasion, with impressive gifts for the lasy. Each year a different state brings the gift, and the year that Carolyn Crawford was State President, she presented 600 chairs for ceremonial use at the statue. Other impressive gifts have been: $50,000 to the American Museum of Immigration located in the base of the statue, furniture for the museum, amplifying equipment, public address system, landscaping, official donor’s registry, and two wheel chairs for handicapped visitors. This year’s gift was a magnificent 20 x 30 foot nylon flat – one of a pair. If it were not for Auxiliaries such as Orrington and the rest of the posts throughout the U.S. none of this would be possible. Says Carolyn: “We are the largest volunteer group in the world.” The Orrington group, Maurice W. Miles Auxiliary was Instituted in 1948, with Mary LeGasse as first president.

As this is Memorial week, we’d like to include this passage from “Little Talks on Great Things,” by Arthur Mee, because it seems to sum up what we’ve been trying to cover about the VFW and the patriots in general: “The great patriots of the world – who are they? Their lives make up the common story of our land, and it is the lives of unnumbered common people, and not of a few heroic figures in the center of the stage, that make a nation. Out of the ranks of the people come the shining heroes. The spirit of sacrifice and service that endures all the time, and the sudden heroism that rises to the great occasion, are elements in that broad basis of patriotism on which the heart of the nation rests. The enduring strength of a country is drawn, not from its dramatic forces or its mighty figures, but from the steady flow of life which never fails, which is always there to be called upon – the reservoir of power which we know can be turned on at any moment to sustain those great causes for which the nation stands. Great men are like comets, sweeping now and then across the sky and startling us by their dazzling light; but the people are like the stars, that shine forever and ever.”

Comments Off on They Refused to be Forgotten (Orrington Gazette, c. 1975)

Filed under Articles

Letters to Board of Selectmen Regarding Grange Hall Windows

Comments Off on Letters to Board of Selectmen Regarding Grange Hall Windows

Filed under Uncategorized

The Closing of Herrick’s General Store (The New Gazette, 1971)

The following excerpts are from the December 16, 1971 Special Edition of the New Gazette, a newspaper published as a community service project by the Orrington Jaycees. These excerpts were transcribed by Pauline Bickford-Duane in July 2017.

THE NEW GAZETTE

Special Edition

December 16, 1971

SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENT

It is with mixed emotions that I make the following announcement: The business of the S.S. HERRICK & CO., also known as HERRICK’S, will cease operation on December 31, 1971.

There has been a HERRICK’S STORE at 590 So. Main Street, Brewer, for 92 years. Last year during the Maine Sesqui-Centennial Celebration HERRICK’S was honored by recognition for being the second oldest grocery store in the State of Maine under continual operation by the same family at the same location. The oldest store was Frisbee’s Market at Kittery Point.

Sewall Herrick started his business in 1879 and served the people for 60 years, then his son Winslow Herrick took over the business, made many changes to better serve the people for 26 years, and then I, Jeanette Wiswell, bought the business and continued the Herrick tradition for six years. I now feel that there is no real need for this type of business and rather than to make changes to conform to the present need, I prefer to retire and enjoy a few years of relaxation and pleasure while I still have good health.

My first thought was to “close out” but on second thought I realized the need of a grocery store on this particular corner and felt that I could continue to serve the people if I could find someone worthy to take over. So – although I am sorry to announce the closing of HERRICK’S, I am glad to announce the opening of MACDONALD’S.

I was very fortunate in finding a young man of good character, Richard MacDonald, a resident of Brewer, and present owner of two grocery stores in Bangor, who was glad to buy my business and is prepared not only to carry on, but to serve you further by changing the store hours to “8:00 A.M. to 10:00 P.M. 7 Days a Week.” He will also employ Frank Phillips to serve you at the meat counter.

So – with my feelings of sadness to leave and my feeling of hope and happiness for the future, I make this announcement.

NOTE: Miss Dagny Erickson, a former schoolteacher in Orrington and Brewer, has written a book entitled “From Norway to Nostalgia” and has kindly permitted us to use excerpts from this book which you will find in this issue of the Gazette.

Jeanette Wiswell

AN INTRODUCTION

Although Herrick’s store had had its beginning many years earlier, it was not till the year 1907 that we came to know it – better than most perhaps. Its history then was well known, and we learned of its start on Main Street, as a sort of ships chandlery business, then expanding its services to provide lumbermen’s supplies and general merchandise. Needing more room, the owners had moved the growing concern to its present location at the corner of Main and Elm. One of its earliest owners was a Captain Drake who later moved to Boston, leaving the young enterprise in the hands of Harlan Sargent. It was at this point that Sewall Herrick came into the picture, and became a partner. However, in the course of a few years, the sign over the door read S.S. Herrick & Co. – changed some years later to S.S. Herrick and Sons.

Every family in South Brewer, and many more in Orrington, had good reason to hold in high regard the convenient, dependable general store and its efficient, friendly personnel. But our family’s position for accurate appraisal and unbiased appreciation was a unique one. Recent immigrants from Oslo, Norway, we found ourselves set down in a strange environment, which was held together by four focal points that spelled security: school, the sawmill, church, and Herrick’s.

The store has been modernized in recent years into an effective, attractive self-service mart, with the necessary refrigerated units and two check-out counters. Nevertheless, it can never reach the picturesque peak of the early decade in the present century.

In my book, “From Norway to Nostalgia,” I have devoted an entire chapter in an effort to do justice to Herrick’s, both then and now. A few excerpts from that may do more to enhance its memory than bare outlines, and cold statistics.

Dagny Erickson

CHAPTER X

DEMOCRACY – FULL MEASURE

Situated across Main Street from our house was a local institution which contributed as much to the Erickson tribe’s early education here as did the school itself. It was that solid segment of small town America called, usually, the “general store.” Standing foursquare on its firm foundation of red brick, it faced the western sky, the wintry blasts, and the ever-growing demands of a population that believed in living well. Over its main entrance hung a sign which read S.S. Herrick and Co. Through its three doorways and within its well-built walls moved and functioned all the elements, all the ingredients of New England democracy at its very best. Over the broad boards of its bare floors, worn splintery and grooved, walked a cross-section of humanity on equal footing. Laborer or lumberman, farmer or fisherman, retired sea captain or limping veteran, each took his turn and was served, according to his needs, with the best available at the time.

Some well-to-do individuals, independent as a “hog on ice,” paid “cash on the barrel head.” Others living on monthly incomes “ran bills,” as did the mill-workers who squared up each Saturday night. Then there were those who, hit by sudden financial emergencies, got behind, but obtained what they needed through their difficult time even if the future, too, looked grim and uncertain.

Unlike many similar places of business throughout this section of the country, loitering was not particularly encouraged at Herrick’s nor was pompous oratory any part of the day’s dealings. Anyone who had a cargo of opinions to unload had to find more willing ears elsewhere. Verbiage beyond the necessary oral order was brief and to the point. Anything more would have been redundant in the face of the proprietor’s own taciturnity. Besides – everyone was much too busy. Occasionally a farmer sat down at the flat-topped stove to warm himself, while his wagon was being loaded at the store-room platform; and if there happened to be a lull in the meat department Mr. Herrick might leave his private domain to enjoy a pipe and the warmth with his customer. But usually the farmer helped to load his feed and grain and household staples himself in order to speed the operation. Very likely he had long miles to cover with his slow team, and to get home in time for mid-day chores or the evening milking was as inevitable – a must – as Franklin’s “death and taxes.”

Children came and went on errands for their elders or to hover over the candy case with sticky pennies clutched tightly in their greedy hands. Each one, in spite of age, sex, or position, had to adhere to the highest standard of personal conduct or suffer the consequences. The rules of decorum for anyone under eighteen were set up and enforced by a peppery spinster who occupied, full-time, the bookkeeper’s cubicle in the exact center of the store.

Perched high on a “Bob Cratchet” stool, she kept most of the store under constant surveillance and nothing within her line of vision went unnoticed. Children were the bane of her existence and it might have pleased her well had the natural order of things provided that adults should arise, full-blown, from the sea like Botticelli’s “Venus.” Little girls, quiet and primly starched, or tousled-headed boys with one knicker leg properly anchored at the knee, the other sloppily dangling halfway to the ankle, got the same fault-finding treatment. If any one of us came precipitously through the door, she accused us of slamming it; a slow careful entry “caused a draft,” a purposeful walk down the aisle to the order desk brought the rebuff, “Get back, you’re in the way.” An indecisive stop, part way between the orange crates and the pot-bellied stove, produced a shrill “What are you doing way down there?”

So, philosophically, we gradually adopted and followed a chalk-line course down the middle of her varied do’s and don’t’s but rarely, on the way out, closed the door behind us entirely unscathed.

Many of the scars on my tender memory healed miraculously one day when I heard her tell a grizzled walrus of a man that he didn’t know his own mind. And he, who had sailed the oceans of the world, in storm and in calm, as mate and as captain, merely shook his head and grunted.

But she had her virtues too. Like the village doctor, she knew the rattling skeletons in assorted closets all over town, but never a hint of gossip was ever laid at her door.

The clerks were kindly men with well developed capacities for patience. This quality was most apparent when we were vacillating between the candy display and the pickle barrel. A penny’s worth of candy meant, at best, no more than two delightful gulps; a huge, sour cucumber, combined with a few crackers, promised at least an hour of careful nibbling. It was a momentous decision and the clerks shared the strain.

Fred Ware was our favorite. He was a deacon at the church and leader of our Junior Christian Endeavor Society. To our benighted souls, his fund of biblical lore made him the fount of all knowledge and as such we properly revered him.

Then there was Abe who lacked all the attributes of manly beauty, besides being extremely sharp-nosed and cross-eyed. We saw little of him, as he was driver of the team that made all the daily deliveries. Mornings he went “up the road,” afternoons, “down the road” and into North Orrington. During the gaps between, he filled orders and worked on his accounts. Not long after our arrival he left the store to take up poultry farming in East Orrington. This change, on his part, brought about the first removal of old landmarks in our neighborhood. The ancient bandstand that had graced the southeast corner of “our flat” for many a long year was carted majestically on a low jigger to Abe’s new property. Here he converted it into a henhouse. Such a come-down for a temple of music!

All the clerks wore hats while at work and I remember Mr. Smith simply because his was a hard straw skimmer of the boardwalk variety. He wore it at a rakish tilt toward his left ear that went well with his dapper, bow-tie personality. His cool nonchalance was the only effective weapon against the bookkeeper’s acid attacks and she found him mildly amusing. Once I actually saw her horizontal lips turn upward ever so slightly at one of his quips. During the tornado, already described, when the clapboards on the flat became airborne, a goodly number of them crashed through Herrick’s plate glass windows, and our Mr. Smith, missing his cue to duck, was badly cut by flying glass. Luckily he was the only casualty.

Sewell Herrick was one of the kindest men I have ever known and that knowledge came to me when I was in a position where every direction was up. Had such a sentiment about him been noised around and come to his ears, it would have roused his mighty wrath. He was essentially a quiet, retiring man who lived the golden rule without the accompaniment of clashing cymbals. Lean, sparse,a graying whisp of a man, compared to my Dad’s towering stature, he seemed made of steel springs and possessed a dry wit which is often an asset of those who think much and listen well. Very likely much of his humor fell on uncomprehending ears, for it became doubly subtle because of his frugal use of words. Whether it was fear or awe, it is hard to say, but none of us ever took any liberties with his abounding good nature.

Under Dad’s first “division of labor” plan it fell to my lot to get our daily supply of groceries. The boys did not fare so well. On general principles, we objected to anything in the nature of a chore because it came under the heading of work. But Ted and Bjarne were more than justified in the struggles against the back-breaking task Dad set for them. Martin was still too young to participate, and besides, he had developed a quicksilver agility about wriggling out of any situation that might involve him unpleasantly.

Dad’s job, which was a sort of piece work arrangement, gave him a fringe benefit which became the boys’ daily duty to collect. In bunching the strappings, which were of varying lengths, Dad had to saw off the protruding ends after the bundle was securely tied with tarred rope. These odds and ends of wood were his for the taking, and as they were excellent fuel for a quick, hot fire they had to be toted home. A heavy iron wheel barrow was borrowed from the mill and then loaded from beneath Dad’s “horses.” It was a long trek to the house, first up over the steep muddy slope from the mill yard, to the edge of a rutted Main Street, through the deep puddles at the town pump and up slopes of a wide valley at the edge of our own strip of front lawn. By the time the shed door was reached, there was hardly enough left of the load to fill the woodbox once. All the way back to dad’s position was a sawdust trail dotted with assorted pieces of glistening “green” wood, so a pick-up trip had to be made lest Dad should follow the well-marked path and object to its convenience. After trundling the barrow himself a few times, he hired a man with a dump-cart to haul us a weekly supply and thus ended one area of “durance vile” for the two boys.

My task of going to the store was not that difficult, but neither was it entirely simple. This was before the days of self-service and a customer at Herrick’s was expected to stop at the order desk, hand over his “store-book” and give his order. This was written down, item by item, in the small ledger carried back and forth, and also scribbled off in the big ledger on the counter. The clerk then roamed around, gathering your supplies while you waited. This method was obviously impossible for me. My vocabulary at that time contained very few English words that in any way pertained to groceries. But Dad had made arrangements at the store so I would be permitted to do my own roaming with a clerk in tow. Pointing to the things I wanted, the entire process went on with few hitches, but completely in reverse.

This was where Mr. Herrick came into my life. When not too busy he attended to my instruction himself but the clerks were told to make me pronounce each item on my list satisfactorily before I was allowed to depart. Just how they managed about quantities is a guess at this time. Perhaps, as every man had his own family and knew well the size of ours, he weighed and measured accordingly.

One morning we ran out of cocoa for breakfast and I was dispatched for another can. The business of the day had hardly gotten into full swing. Mr Herrick was free and waited on me himself. Proudly I asked for cocoa, making three syllables of it, and probably, Scandinavian style, saying “coo-coo-a.” A shrill cackle from the bookkeeper’s cage was evidence enough that my error was grotesque, and that I should, as usual, have pointed to the familiar “Lowney’s” label. With infinite patience Mr. Herrick drew a finger nail across the “a” as if to lope it off. Then taking me to the corner where the shelves of canned vegetables jutted against the bakery case he made similar imaginary lines through the a’s in bread and peas. It was my first lesson in the intricate pattern of English spelling where silent letters lurk to beset the path of the unwary.

At another time, in those earliest days, I was sent to get a scrub brush. Our soft wood floor had become hopelessly gray and Mother was on a cleaning spree. Up to this point, I had managed nobly and knew every inch of the store better than any other youngster in town. However, I could not remember seeing any brushes anywhere, so it was necessary to appeal for help. My pantomimes were “Oscar” winning performances but produced no results. Finally a clerk opened the cellar door with a “be-my-guest” gesture, and there, hanging in clusters against the sloping wall were brushes of every sort including the kind I desired. After a valiant struggle with the collection of consonants in the two words, I crossed the street in triumph.

From the front entrance, the interior of the store may have looked a bit like a repository of heterogenous abundance. However this was not so, for the planned lay-out was both simple and logical. In general, the front of the store was the housewife’s province, while in the back could be found the manly things her spouse might want.

To the left, as one entered from Main Street, a swinging screen door opened into the dry-goods and hardware department. This was a long, narrow room in which could be found oil cloth, screen netting, workmen’s canvas gloves, shoe lacings and a glass case of assorted thread. To this last, I came often and soon learned that the bigger the number, the finer the thread. Mother used no. 60 for fine sewing but bought a prodigious amount of no. 12 to sew up rips and tears, attach patches, and replace buttons in a desperate attempt to keep them secure, for more than twenty-four hours at a stretch. As for hardware there was a profusion of pots, pans, pails, tubs, lamps and lanterns, rows of bean-pots, and way up high, a line of chamber mugs.

The main store had one long counter on which were set a number of glass cases. The first of these was the tobacco case filled with plugs of both chewing and pipe tobacco. Here too, were cigars in beautiful boxes. These we much admired because on the inside open cover were colored pictures of buxom Spanish ladies with roses in their hair or between their very red lips. Usually a draped skirt was daringly lifted to display a generous view of ankle and leg. Somehow I obtained one of these prized wooden receptacles and used it to keep my hair ribbons in. The faint aroma of tobacco that clung to my person bothered me not a whit.

Back of the counter ran long shelves, well stocked with spices, extracts, patent medicines, polishes and boxes of small hardware. Along the front were crates, barrels, bins, and kegs of products from far and near. Sponges from tropical waters lay neighbor to greens from Hersey Smith’s farm; apples from Orrington blended their spicy fragrance with the citrus fruit perhaps from the Mediterranean; and in the window, hung great bunches of bananas adding color to the baskets of local potatoes and turnips that sat underneath. Once, at Thanksgiving time, a tremendous barrel made its appearance near the orange crates. It was filled with ground cork and when a clerk reached down deep he came up with immense clusters of luscious, pale green grapes. I’ve wondered many times since, did they come directly from southern Spain or Portugal where such fruits are grown and where the cork-oak tree is indigenous?

Near the big round stove stood the bakery cabinet, not very large, for most housewives did all their own baking. Store bread, sugar or molasses cookies, and “boughten” doughnuts were strictly for rare emergencies or for housekeeping bachelors. Beyond the bookkeeper’s cage was the meat room at one side and another long counter on the other. At one end of this counter sat a great round cheese under a glass dome. It was a source of great interest to see how accurately any of the clerks could cut a wedge for a customer. Seldom did he go over or under the desired amount by more than a tiny fraction of an ounce.

There was a time when the church, the school, the doctor’s office, and the local store, jointly, made up the core of every close-knit community. But the general practitioner has become a specialist and has moved out of his dingy office and the heart of the people, and into sterile clinics or up-to-date medical centers. It would be a rare one who could thank you for mussing up his natty appearance by crying on his shoulder. Modern super markets and expanding shopping centers are snuffing out the life of the small independent grocer. We are swapping the friendly shopkeeper, who not only served his community but loved it, for bits of human automation, called check-out girls, who speed you on their way with their mechanical smiles. These changes are taking much of warmth and color from the American scene. It is too bad that the wheels of progress not only grind, but sift. Only the practical is retained; left behind are the dying embers of a glowing vitality that sprang from a sincere personal concern, one for the other.

It was my great good fortune to discover Mr. Sewell Herrick and to hear the beat of the great big heart that lay just south of the stained clay pipe usually gripped between his teeth. Under his loose vest, that generous organ was often called upon to extend itself to a troubled customer and make him a friend-in-need. And that is the image that remains with me.

Mother died on August 20. The months that followed were difficult for all of us but especially so for Dad. Not only was he left alone to cope with a family of children, but a mountain of bills had piled up to confront him. Three funerals to pay for – our two young sisters had died too – doctor’s fees and all the attendant costs, besides our daily living expenses, totaled to a financial burden that sent Dad to his work at day break and kept him there till dark. When the saw mills closed down at the first sign of ice in the cove in late November, Dad looked thin and drawn. But he took his usual winter job in the beater room at the pulp mill and continued to face his problems with cold stoicism. As the winter approached his health became worse. No matter what he ate it hurt him, and he lay around, during his brief leisure, in utter lassitude with faint pink spots tinting his cheeks. The day finally came when he was unable to drag himself out of bed, let alone attempt to tackle his daily toil. So on the advice of a good neighbor, I called the elder Dr. Thomas who came at once as he had so many times before. His diagnosis was swift and his orders peremptory. Dad had typhoid fever and the hospital was the only place for him – and at once.

The good doctor waited until the ambulance arrived, meanwhile giving me advice about how to clean Dad’s room and what to do about the heavy bedding.

As Dad was being carried out, feet first, on a stretcher, through our seldom-used front door, all the long series of family catastrophes gathered into one mighty wallop that landed squarely on my rounded thirteen year-old shoulders. Reeling under the impact, I fell against the door frame. With my forehead on the cool panel, I cradled my face in my hands and sobbed uncontrollably. The hopeless tears bounced off my bony cheeks and splashed on my stringy, tired arms. The man at my side, accustomed to grief and despair, placed his hand gently on my bent head and left, closing the door quietly behind him.

It never occurred to any one of us that Dad might die and that his tall frame would never again walk in at the door. To us he was indestructible and an ever present force to be reckoned with. No, my greatest worry those gloomy winter days was the staggering balance in our store-book. Nearly one hundred dollars! Einar was working, earning a dollar and a quarter per day but our supplies averaged at least twelve dollars a week. By cutting corners here and there, I tried to keep it below ten. But we were young, hearty, and always ready to eat, so the struggle was a losing battle. All at once, going to the store became a much dreaded necessity. Instead of saying, “I want this, and this, and this” I was pleading ungrammatically but humbly “Can I have…” Each day I expected a thunderous “NO.” Then it happened. The clerk at the order desk said, “Mr. Herrick wants to see you in the meat room.” I moved toward the swinging screen door much as Marie Antoinette must have moved toward the guillotine, except that the ill-fated queen carried her pride high and mine was trailing in the dust at my heels.

Mr. Herrick was wielding a cleaver as I entered so my gory simile is not too inept. But he laid it down, pulled his lank person up onto the edge of the chopping block, fondled his pipe and looked at me meditatively. And then he made what was, perhaps, one of his longest speeches. It is impossible now to quote him verbatim but the gist was clear.

The doctor had told him that Dad would be as good as new but that he would need good food and plenty of it. He (Mr. Herrick) explained that he and Dad had made a deal in the fall whereby Dad could pay off all his other bills first, letting his store account run until the following summer. Mr Herrick was troubled because I was cutting down on amounts. “A pound and a half of meat is not nearly enough for five of you, and why don’t you get eggs and fruit?” he scolded. Then, “We’ll keep your store-book here, then you won’t fret about it. Get what you want, all you want at any time. The saw mills will start again by the time your father is well and he’ll clean up his account in no time.”

I won’t wax so poetic as to say I walked home that day with my head up and a song in my heart. But I did clasp close to my ribs a substantial bundle of pork chops. From then on, my order would often be augmented by a bag of doughnuts, sugar cookies, or a wide “hand” of bananas. Whether he ever listed these extra items in our account I shall never know.

Best of all, his predictions were right. By the time the mills whistled again, Dad’s health was the best it had ever been. The horrible figures in our store-book dwindled gradually to zero and again things were reasonably right in our little world.

May the name of Herrick be blessed to the fourth and fifth generations.

Comments Off on The Closing of Herrick’s General Store (The New Gazette, 1971)

Filed under Articles

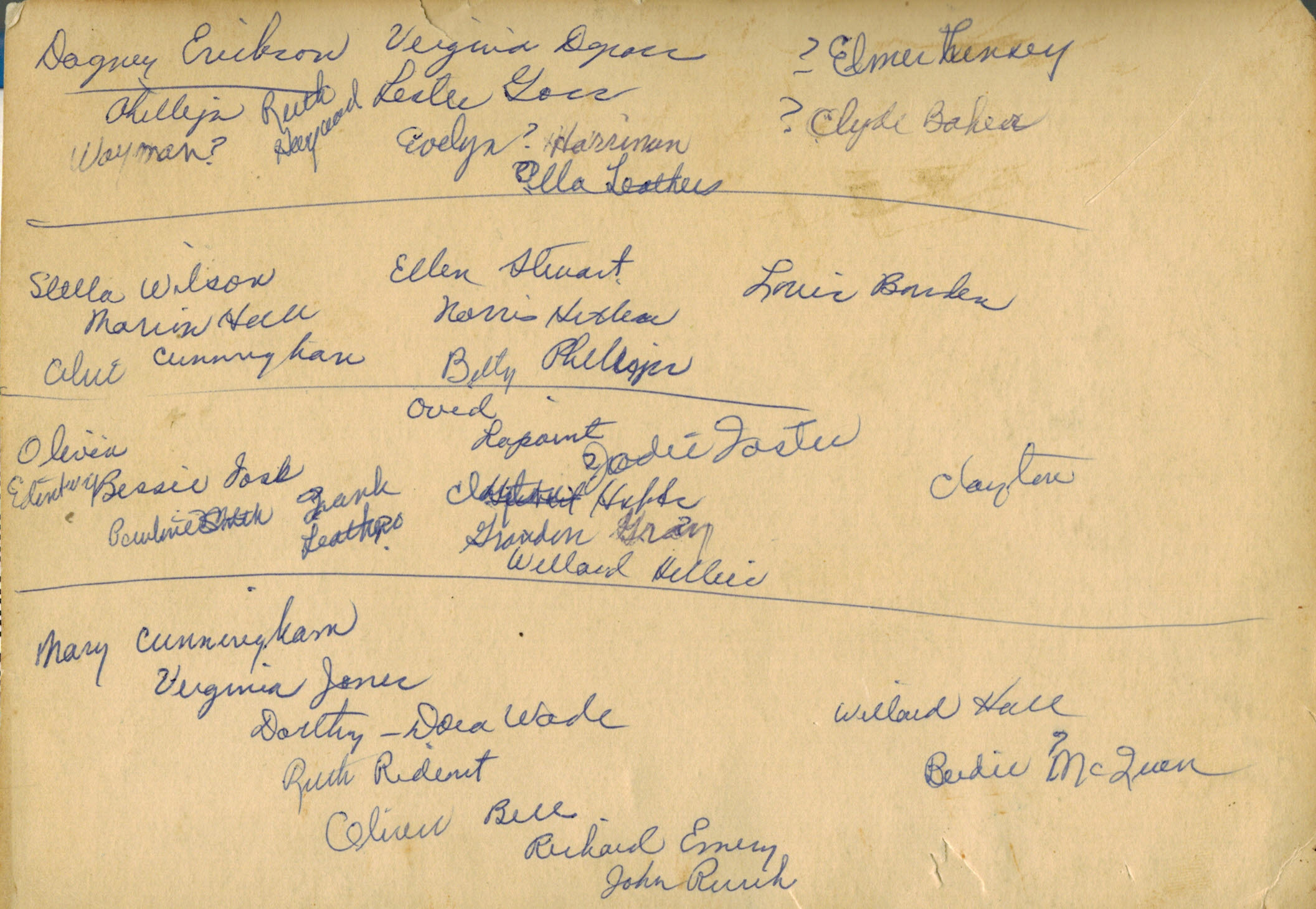

North Orrington Grammar School, 1928

Names on the back of the photo:

Dagney Erickson, Virginia (?), ?Elmer (?), Phillip Wayman?, Ruth Haywood, Leslee (?), ?Clyde Baker, Evelyn? Harriman, Ella Leathers

Stella Wilson, Ellen Stuart, Louis Bowden, Marvin Hall, Norris (?), A(?) Cunningham, Billy Phillips

Olivia (?), Oved Lepoint, Jodie Foster, Bessie (?), Cl(?) Hyde(?), Clayton, Pauline Smith, Frank Leathers, Granden(?) Gray, Willard (?)

Mary Cunningham, Virginia Jones, Dorothy – Dora Wade, Willard Hall, Ruth Rideout, Colin(?) Rice, Birdie McQueen(?), Richard Emery, John (?)

If you recognize any of these names and would like to submit a correction, please comment below or email info@orringtonhistoricalsociety.com.

Filed under Articles

THE NEW GAZETTE: “New Orrington School” by Robert Woods

THE NEW GAZETTE

PUBLISHED AS A COMMUNITY SERVICE PROJECT BY THE ORRINGTON JAYCEES

VOL 1 NO 15

“Read by over 800 Families”

Sept 26, 1963

Transcribed by Pauline Bickford-Duane 07/03/2017.

New Orrington School

by Robert Woods

Many people in town are asking questions concerning the new school. This article is being written to help answered by the events of the future.

I would like to describe some of the work that is being done, and will be done in the near future. If any of you have seen the new school, you can verify what is said here.

A trip there today would show us the total frame standing high, alone among the autumn trees. The frame is completely boarded in and in some places is covered by the natural redwood siding. The roof is covered and can be completed with a few days of work by the roofing crew.

Today the wind blows through the empty slots which soon will be filled by many window cases. In a few months many bright, alert, happy faces will be looking out these windows into the blue sky.

Over the floors that will be completely poured by Tuesday, September 17, and covered by asphalt tile, will walk one hundred and seventy children into six of the eight classrooms. Those extra two classrooms will be filled in a few years.

What does the school contain in the way of rooms is one question many people ask. Let’s take a look at the school as we drive in. The cafeteria comes into view as we first see the school. This cafeteria most people hope can be turned into an all-purpose room for the school and town. Many people wonder if this room will fit all uses that can be made of it. Is it large enough for graduation, town meeting, town suppers or dances, and other town and school functions. Here again is a question that can be answered only by time.

The other rooms in the school are a kitchen, with a boiler room under this, janitor’s storeroom, teacher’s room, principal’s office and eight classrooms.

At this date the building committee is pleased by the progress made towards the completion date at the end of November.

I am sure the completion of this will be a welcome event by the people of the town of Orrington. The school at North Orrington which can hold comfortably 360 pupils is being forced to hold 429 students. The children must carry their dinner trays upstairs and eat off the same desks they study at. What a relief it will be for the children not to have to continue this procedure!

Even though the new school will solve many problems there are still a few problems left that will arise because of it. One might be, how much landscaping will have to be done around the school to keep the ground in good solid condition. Another one could be, how much work has to be done on the driveway and main road to bear the heavy pounding by trucks and buses going to the school.

I hope this article has given many people a closer look at the new school and the progress being made. In closing, I will pose one last question for everyone to think about. What will be the name of the new school?

Comments Off on THE NEW GAZETTE: “New Orrington School” by Robert Woods

Filed under Articles

The Launching of the “James E. Coburn”

by John Wedin

from material submitted by Evelyn Ryder Prior

Transcribed by Pauline Bickford-Duane 6/27/2017

The advent of World War I brought about a tremendous demand for American shipping tonnage. Many large ships were constructed on the Penobscot and one of the largest was built at the South Orrington shipyard.

The location of the shipyard in South Orrington was ideal – direct access to the river, good oak and pine available, and most important in any enterprise – excellent skilled labor available in the immediate area. The yard was leased from Captain C.W. Wentworth of South Orrington.

In 1918 the Boston and Penobscot Shipbuilding Company was incorporated with offices in Boston, Mass. Mr. Don Sargent of South Brewer was made General Manager and in that year it was decided to begin construction on a four-masted general cargo schooner.

In July, 1918, work started on the four-masted “James E. Coburn” in South Orrington. About 90 men were working on the “Coburn” with about 40 men supplying oak and pine planking from the nearby sawmill supervised by Roy Clark.

Ruel Dodge was the Master Builder, Daniel DeCourcey of Bucksport, scientific blacksmith; George Getchell of Brewer, liner; Edward Snowman of Bucksport, master caulker; Herbert Hoxie, South Orrington, boss painter; Henry Gardner of Castine, rigger; S. L. Treat of Bar Harbor did the lettering; Amos Simpson of Searsport did the joiner work and spars were made by Sidney Hathorn of Bangor.

The “Coburn’s” frame was of native oak, and her planking and ceilings were made of hard pine. The spars were of Oregon pine and the fore and aft houses were finished in natural sycamore, oak, and cypress.

She had four staterooms, a chart room, pantry, engine room, and the captain’s room. The “Coburn” had two anchors weighing 4100 and 3600 pounds supported by 180 fathoms of 1 ⅞” chain. She was 228’ over all, with a 39’6” beam, a 175’ keel, and 19’ depth of hold. The “Coburn” weighed 987 gross tons and had a capacity of 1700 tons.

She was painted white with a red stripe and blue waterways. The lettering on the stearn and bow were all done in gold leaf. The “Coburn” flew the flag of Rogers and Webb of Boston and was commanded by Captain James F. Chase of Machias who stayed at the yard from January through July, 1919 during construction.

It was quite a day on July 15, 1919 when the “Coburn” was launched. Many people from Bucksport, Bangor, Brewer, and Orrington were on hand. As the “Coburn” started to slide down the ways she stuck half way, to the surprise of the crowd. Many seafarers present predicted a terrible end for the ship after such a bad omen at launching. Several days later she was launched successfully and was towed to bangor for final fitting and chartering.

Days later the “Coburn,” with full sails set, eased her way down the Penobscot River and out to sea.

On April 1, 1929 she cleared Baltimore with a cargo of coal bound for Port de France, Martinique, and Port au Prince, Haiti. Twelve days later she passed Cape Henry and on April 17, the “Coburn” was battling for her life in a terrible storm. Later during the day she floundered beneath the waves.

Nine of the crew were saved after being adrift for over a week without food or water. One crewman was lost. So was the end of the “James E. Coburn.”

Comments Off on The Launching of the “James E. Coburn”

Filed under Articles

A Gazetteer of the State of Maine: Orrington (1886)

The following is an excerpt from A Gazetteer of the State of Maine, with Numerous Illustrations (1886) by Geo. J. Varney, author of “The Young People’s History of Maine,” member of Maine Historical Society, etc.

Transcribed by P. Bickford-Duane, August 2016.

Orrington is the most southern town in Penobscot County. It is situated upon the eastern bank of the Penobscot, about six miles below Bangor, on the Bucksport and Bangor railroad. Orrington is bounded on the north by Brewer, east by Holden, and east and south by Bucksport, in Hancock County. The surface is rather hilly and rocky in many parts, but has a fair quality of soil which yields well under thorough cultivation. There are many good farms in this town, and many very attractive residences. A drive along some of its roads is delightful. Orrington Great Pond, formerly Brewer Pond, lies on the eastern line of the town, and with a smaller connected pond on the north, gives a water surface of about 10 square miles. It discharges through Segeunkedunk Stream into the Penobscot in Brewer, just over the north line of Orrington. This stream furnishes at East Orrington power for a saw-mill, and a short distance below for a shingle-mill and tannery; then by successive falls, for two grist-mills and another saw-mill. In the southern part of the town lies Sweet’s Pond, smallest of the three, sending its overflow into the Penobscot at the village of South Orrington. At this place are two lumber-mills and a grist-mill. Other manufactures in the town are drain-tile, earthen-ware, churns, boots and shoes, etc.

The first settlement in Orrington was made by Capt. John Brewer, from Worcester, Mass., in June, 1770, at the mouth of the Segeunkedunk Stream, where he built a mill. He had obtained consent of the General Court to settle here upon condition that he should receive a grant of the territory from the crown within three years; and with his associates, he caused the exterior lines of a tract large enough for a township to be surveyed. They had sent to the king a petition, and a grant was promised; but just then news of the battle of Lexington was received, and the patent was not issued. During the war, Brewer and other settlers were annoyed by the British from the river below to such an extent that they left the place, returning when the war closed. In 1784, the township was surveyed by R. Dodge, and on March 25th, 1786, Captain Brewer, with Simeon Fowler (who had settled three miles below in what is now Orrington) purchased from Massachusetts for £3,000 in joint notes, the lots abutting on the river, to the extent of 10,864 acres. The residue of the township was granted to Moses Knapp and his associates. Many of the first settlers were mariners, who had been forced by the approach of war to seek other business; but navigation reviving on the return of peace, many of these returned to their old pursuits, taking with them their grown-up sons. Previous to its incorporation as a town on March 21, 1788, the settlement had borne the name of New Worcester, or Plantation No. 9. The town was named for Orangetown, Md., but, by a misspelling in the act of incorporation, the name became Orrington. The first representative to the legislature was Oliver Leonard, in 1798. The centres of business are Orrington, on the river near the middle of the town; East and South Orrington, the last being the largest. At Goodale Corners, in the south-eastern part of the town, is an excellent nursery; and the town abounds in fine orchards. There were first erected in Orrington two meeting-houses seven miles apart, and equally distant from each end of the town. There is now a Methodist church at Orrington village, at South Orrington and at the Centre, and a Congregational church at East Orrington. The town has some excellent schoolhouses, the entire number being thirteen. They are valued at $4,975. The population in 1870 was 1768. In 1880 it was 1,529. The valuation of estates in 1870 was $400,839. In 1880 it was $405,898.

Comments Off on A Gazetteer of the State of Maine: Orrington (1886)

Filed under Articles